In a modest workshop in Addis Ababa, master sculptor Dereje Yehualashet bends over a single block of wood, shaping it with steady hands and unwavering focus.

The room is quiet except for the sound of carving tools meeting timber.

There are no gallery lights or international collectors present, yet the work unfolding here carries the weight of history.

Each sculpture begins as raw material and slowly becomes a story. Each angle is measured with care. Each detail is refined through patience and discipline.

Dereje carves his sculptures from a single piece of wood, a method that demands precision and endurance.

“Every angle has to be perfect,” he told Bantu Gazette, explaining that a large sculpture can take more than a year to complete.

Sculpture, he said, is “100 percent handmade,” requiring work day and night.

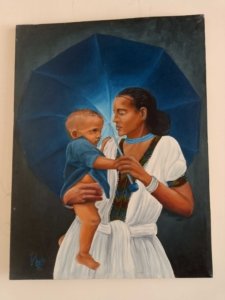

His pieces draw from Ethiopian history and spiritual symbolism, including a monumental representation of the Victory of Adwa, the 1896 battle in which Ethiopia defeated Italian colonial forces and preserved its sovereignty. The victory remains a powerful symbol of African resistance.

“All the artworks we are building represent Ethiopia and Africa,” he said. “We are building art that represents Africa entirely.”

Preserving History Through Art

For Dereje, sculpture is both a cultural preservation effort and a personal mission, reflecting what he describes as a deeper meaning behind his work.

“These sculptures are living cultural treasures for future generations,” he said, adding that they also hold untapped economic potential.

He described his motivation in simple but powerful terms. “There is no giving up,” he said. “I sacrifice time that I should spend with my children just for creating an impact.”

His ambition reaches beyond the present moment. He shared his dream of creating a record-breaking monument that represents his country on a global scale.

“To achieve it, I pay all the sacrifice it takes,” he said. Even after the closure of Miracle Sculptures and Art Studio due to limited market access, he never stopped creating.

The studio may have closed its doors, but the vision behind it remained alive in his hands.

The Reality Behind the Craft

Speaking about his work, sculptor and painter Ermias Dereje shared similar perspectives, emphasizing the cultural weight and personal meaning behind his artistic practice.

He described his journey into art as beginning with a childhood competition that awakened his confidence and set him on a professional path.

Over nearly a decade, he refined his skills through practice, competitions and commissions. His love for art, he said, always came first.

Income followed later and often unpredictably.

Ermias offered concrete insight into the investment behind each sculpture. A medium- to large-sized wooden or stone piece can cost between 5,000 and 20,000 Ethiopian birr (about $30 – $130) in materials alone.

Beyond that are months of labor, often requiring 80 to 120 full days from concept to completion.

“People see the final object but not the months of life and resources poured into it,” he said.

In the local market, he explained, it is difficult to price such work fairly because many admire it but do not purchase it.

Talent Without a Market

Both artists described a common challenge. Dereje stated plainly that “the main challenge is lack of market access.”

He explained that international exhibitions often require quotas for sculptures of different sizes, which is difficult to meet without consistent sales.

Without revenue, production slows. Without exposure, opportunities remain limited.

“Without an audience that values and purchases art, art loses its worth,” Ermias said.

He added that admiration alone is not enough. Internationally, art is treated as an asset, with collectors competing in auctions and investing seriously.

Locally, exhibitions may draw praise, but praise rarely translates into purchase.

As he put it, “You must sell it and at the right value. Otherwise, you would rather starve than sell your work cheaply.”

A Collection Waiting for Its Moment

Despite these constraints, the artists remain prepared. Ermias confirmed to Bantu Gazette that he currently has five major sculptures that are ready for exhibition and stored securely.

In addition, he has at least a dozen more works in progress, many about 80 percent complete.

He explained that he often leaves the final 10 percent unfinished until an exhibition is confirmed, so the sculpture appears new and alive at its debut.

Dereje also continues to create from his home workshop, though he described the space as a major constraint.

Still, he views the collection produced at Miracle Sculptures and Art Studio as a cohesive body of work.

“My intention is to leave a legacy,” he said. The pieces are connected by a shared goal of representing Ethiopia’s culture and history for future generations.

Together, they form what could be seen as a hidden national gallery, preserved not in a museum but in storage rooms and private studios.

Africa’s Expanding Art Horizon

Their stories unfold at a time when the broader African art market is gaining international recognition.

The African contemporary art market has become a significant segment of the global art trade.

According to the Artnet Intelligence Report 2024, auction sales of works by African-born artists reach tens of millions of dollars annually, with leading figures such as El Anatsui, Julie Mehretu, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Amoako Boafo achieving multimillion-dollar results at major auction houses.

At the same time, ultra-contemporary artists under 45 account for the highest sales volumes, often at more accessible price points, reflecting strong demand and a broadening collector base.

Despite this momentum, African artists still account for a small share of global contemporary art sales, underscoring substantial growth potential in the years ahead.

For Ethiopian sculptors, this moment represents possibility. The talent, discipline and cultural depth are present.

What remains is greater visibility and connection to audiences who understand art as both heritage and investment.

A Call for Unity and Collaboration

“Collaboration is no longer optional. It is essential,” Ermias said.

He proposed the creation of professional, curated exhibition spaces at major diplomatic hubs, where international visitors could not only admire but also purchase artworks.

He emphasized that artists are ready to deliver high-quality work when provided with structured platforms and logistical support.

Dereje shared a similar hope regarding pan African platforms. “If the African Union provided a pavilion, it would be a major breakthrough,” he said, noting that such exposure would benefit not only individual artists but Ethiopian and African culture as a whole.

In workshops across Addis Ababa, chisels continue to rise and fall against wood and stone.

The artists are working, refining, preparing. Their sculptures carry stories of Adwa, faith, sacrifice and aspiration.

Whether displayed locally or on international stages, they stand as testaments to Ethiopia’s enduring creative spirit.

The renaissance they envisage is already being carved, one careful strike at a time.

Bantu Gazette contacted the Ministry of Culture and Sports for comment on support structures for sculptors and potential exhibition platforms, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

By Abel Gorfu Asefa

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia